Reinhabit Maui!

Reinhabit or Re-inhabit. Verb. 1. To become rooted in a place by getting to know it deeply, especially via first-hand experience. 2. To heal or restore a place that has been disturbed or overexploited. 3. To bring culture into sustainable alignment with local ecosystems. Also: reinhabiting, reinhabitation, reinhabitant, etc.

“Reinhabit” is a wonderful word – one of my favorites, and much underutilized. The term has been been around for 40 years or so, but given our current situation here on Maui and on the planet this is a good time and place to reflect on its meanings.

Reinhabit is a welcoming word, inviting each one of us to deepen our individual connections with the place where we live. This can be pursued on different levels: mental, physical, spiritual, artistic, political. For me the connotation is unconditionally positive and life-affirming, like a word of encouragement spoken by an elder, or by the local bioregion itself. It carries an implicit understanding that much of humanity has become estranged from the planet and the specific places where we live – the river valleys, islands, foothills, or plateaus. But rather than scorning us ecologically-wayward souls, reinhabitation encourages and inspires us to get back on the path. Here is some of the terrain that path winds through.

Reinhabit is a welcoming word, inviting each one of us to deepen our individual connections with the place where we live. This can be pursued on different levels: mental, physical, spiritual, artistic, political. For me the connotation is unconditionally positive and life-affirming, like a word of encouragement spoken by an elder, or by the local bioregion itself. It carries an implicit understanding that much of humanity has become estranged from the planet and the specific places where we live – the river valleys, islands, foothills, or plateaus. But rather than scorning us ecologically-wayward souls, reinhabitation encourages and inspires us to get back on the path. Here is some of the terrain that path winds through.

Place-based learning. Reinhabitation starts with real, detailed local knowledge. If you were born and raised here, close to the land, you may have been steeped in this knowledge from an early age. In that case, maybe there’s no need for you to re-inhabit, just keep on inhabiting. Most of us, however, were either born into or swept up in a consumer culture and a car-based lifestyle where we move past the local landscape more often than we are in it.

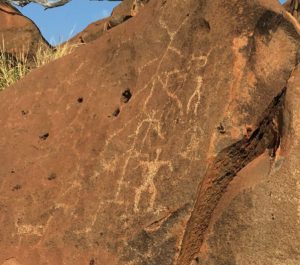

Local knowledge has many forms and can come from many sources: lingering on old writings and photos, studying topographic maps, and listening to elders. Understanding the impacts and legacy of colonization. Learning the ahupua`a and moku names and their boundaries. Studying traditional Hawaiian values. Knowing where the old footpaths were and where the railroad used to run, knowing where one’s water comes from and where one’s wastes go.

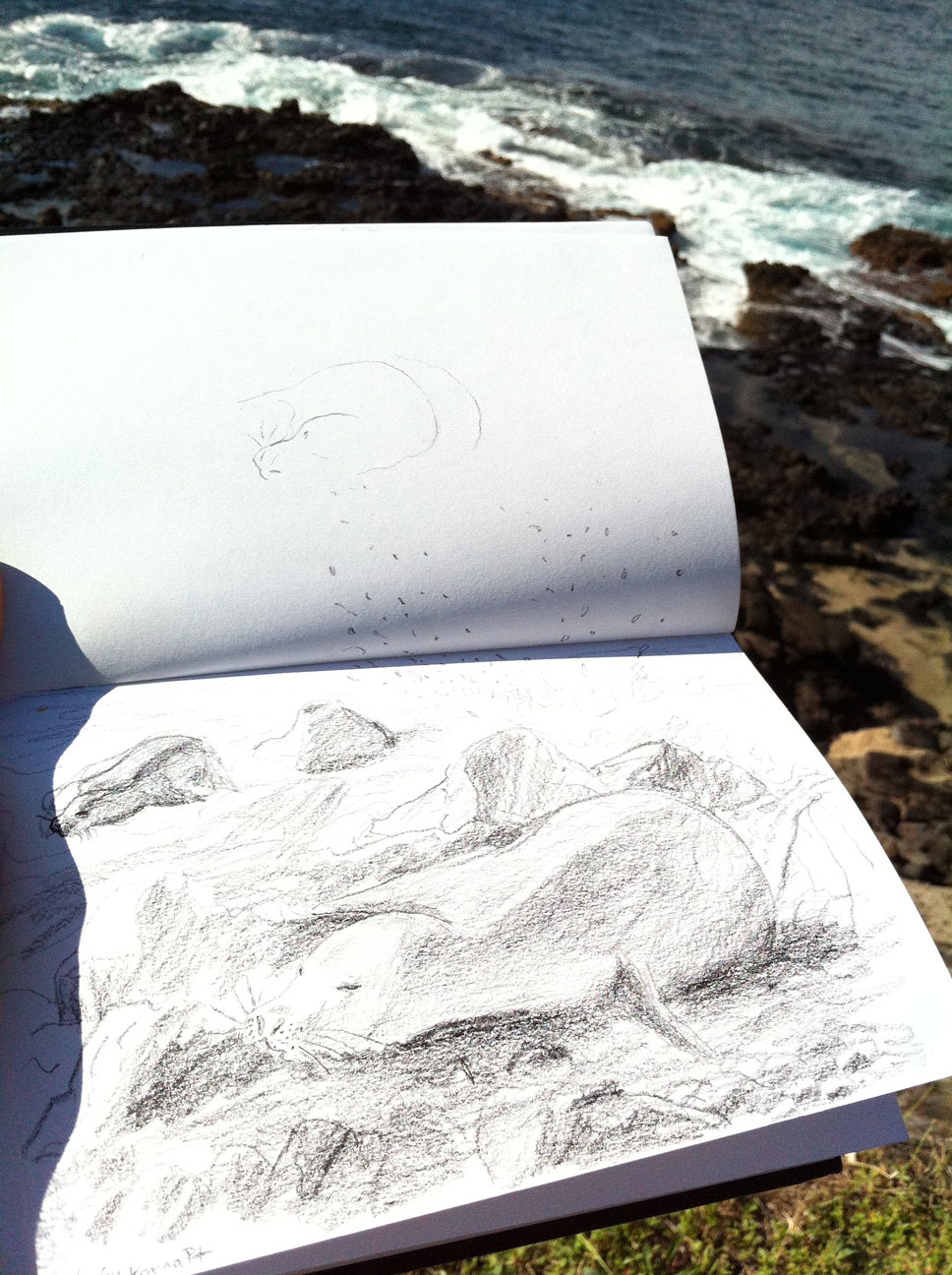

Indispensible to gaining firsthand local knowledge is spending long hours out in the land or sea, under the sky, night and day, in all moods and seasons, in fair weather and foul, paying attention, and seeing patterns. Learning the native placenames and their meanings is time well-spent, the names of peaks and valleys, streams and falls; also flowers and shrubs, bird songs, constellations, and weather patterns.

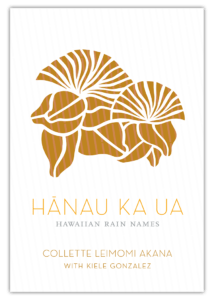

Hawaiian language and culture continue to instruct and inspire in this regard. The recently published Hānau ka Ua: Hawaiian Rain Names by Collette Leimomi Akana and Kiele Gonzalez identifies over 200 Hawaiian names for specific types of rains. Says Akana, “Our kūpuna knew when a particular rain would fall, its color, duration, intensity, the path it would take, the sound it made on the trees, the scent it carried and the effect it had on people.” That is rich knowledge from a culture finely attuned to the local environment.

Hawaiian language and culture continue to instruct and inspire in this regard. The recently published Hānau ka Ua: Hawaiian Rain Names by Collette Leimomi Akana and Kiele Gonzalez identifies over 200 Hawaiian names for specific types of rains. Says Akana, “Our kūpuna knew when a particular rain would fall, its color, duration, intensity, the path it would take, the sound it made on the trees, the scent it carried and the effect it had on people.” That is rich knowledge from a culture finely attuned to the local environment.

Local learning can be a lifelong pursuit, with each day providing new opportunities right at one’s doorstep. It needn’t cost anything, and the rewards are rich.

Physical engagement. In-place learning goes beyond mere observation and thought to physical engagement: using an o’o to move a heavy rock or dig holes for planting bananas, dropping into a perfect wave, or digging up ʻuala at just the right time. With time, one’s skin, hair, muscles, physiology, and the subtleties of one’s sensory experience are all shaped through the interplay with place. Hiking in the crater and sleeping out under the stars. Sharing hā, breath, with a surfacing koholā off Makena or Olowalu.

Then there is the physical act of ingestion. What happens when we eat locally? Eating from the local land and sea we become local creatures, functioning parts of the ecosystem, tasting, swallowing, and metabolizing place. The more one eats locally, whether munching an ʻākala or ʻohelo berry along the trail, harvesting bananas and lilikoi from the yard, or swallowing an unintended gulp of seawater, the more we literally become of this place. Incidentally ingested soil microbes become part of our intestinal microbiome, helping us break down and absorb nutrients, and linking our own dark interiors to the realm of earthworms, the rhizosphere. The molecules of poke and poi we eat become the molecules of our own flesh and blood, bones and brains. In that way our very thoughts and our words are threads in the fabric of this evolving place.

Collective engagement with place: Reinhabitation takes on added meaning as a shared experience, and is both fun and satisfying. This can take the form of hands-on volunteer work in nature: maintaining trails, counting whales, or protecting hawksbill turtle nests. There is also always a need for beach cleanups, native forest restoration for kiwikiu habitat, and removing invasive plants like Himalayan Ginger. Or there are cultural projects like supporting Hokulea and the Polynesian Voyaging Society, or helping groups who are restoring taro lo`i or fishpond walls. Laulima projects bring together work parties to build permaculture landscapes.

Yet group efforts don’t all have to be hard labor. Celebrating and simply enjoying one’s place are healthy for heart and soul: paddling canoe, practicing hula, joining with others in kanikapila.

Both working and playing together hold great potential for crossing cultural divides and building unity for our common cause: our future and Maui’s future.

Spiritual engagement. With time, mere information can ripen into true knowledge. With more time, the mental, physical, and collective forms of engagement with place can evolve into something deeper. Intimacy with, and love for a place can enter the realm of the sublime. While everyone has their own sense of the sacred, what often works for me is a mix of contemplation, curious attentiveness to what is, and an openness to grace.

Out snorkeling along a rocky stretch of coast recently, I saw from the corner of my eye a large shape gracefully emerge from a sea cave beneath me. I then found myself eye-to eye with an upright monk seal that was around my height. For some long moments we lingered there, shafts of shimmering light dancing around us. Just a couple of beings, sharing a moment on a spinning planet, circling around a star in one of the billions of galaxies -- that’s all. I witnessed whatever strange sense of distance I unconsciously carried as a ‘superior human’ melt away. This was replaced by an awareness that I was in the company of a dignified and intelligent being. That woke me up. For a time, the heavy curtain that separates me from the enchanted quality of this place and the creatures around me was lifted.

Speaking of curtains and veils, there is also a certain late-afternoon phenomenon that occurs above the mid-slope meadows and shrublands of Haleakala (best viewed by a small group of observers that are lying on their backs among the māmane and pukiawe). It starts with a few tattered wisps of condensing water vapor, rising up in a spiraling vortex, dancing with one another around some invisible axis, until gradually they are woven together into a cloud proper. If your timing is right, there may be some fleeting moments when the entire cloud nursery is lit up with a brilliant orange-pink glow. And if your luck continues to hold, a pueo may pass overhead, emerging from the mists for just long enough to lock its gaze with yours, and bark a single call note in your direction.

Beyond the memorable and transcendent experiences to be had in nature are an infinity of more subtle ones to behold and contemplate. Perhaps most worth contemplating is the sheer awesomeness of how many things are happening all-at-once, how they all fit together, and how the whole dynamic matrix of person, place, and planet are in continual cosmogenesis, self-organizing from within. That alone is worth an offering, a prayer of gratitude, or at least a slow deep breath into one’s center, the na’au.

Toward a culture of reinhabitation

As we wind down this meditation on reinhabitation, we shift our gaze toward Maui’s future. So far we have explored local learning, getting one’s hands in the soil, building community, sinking roots, and celebrating the subtle, mysterious, and life-giving dimensions of our island home. The underlying threads here are a deep love for this place – aloha `āina – and a respect for the culture that evolved here over many centuries. That provides a firm foundation for building our shared future upon.

As we wind down this meditation on reinhabitation, we shift our gaze toward Maui’s future. So far we have explored local learning, getting one’s hands in the soil, building community, sinking roots, and celebrating the subtle, mysterious, and life-giving dimensions of our island home. The underlying threads here are a deep love for this place – aloha `āina – and a respect for the culture that evolved here over many centuries. That provides a firm foundation for building our shared future upon.

Building a culture of aloha `āina and reinhabiting Maui will mean traveling together down a number of winding and intersecting paths:

- defending what we value and love

- envisioning a healthy future

- organizing and working to create that future.

The energy-intensive consumer culture is clearly unsustainable, yet for now it keeps marching forward. Here on Maui that means much of what is beautiful and special about the island is under threat and needs defending: coral reefs, native forests, agricultural lands, beach access, Hawaiian culture, and the ‘regular people’ that would like to have a decent livelihood and an affordable place to live. Defending this place means working together, taking a stand, resisting harmful practices and policies, and being seen and heard.

Even though it may sound like the easy part, envisioning a healthy future can be surprisingly difficult. We are often conditioned so strongly by how things are that visions of a truly healthy local future may sound simplistic. Unrealistic. Annoyingly idealistic. Besides, for those of us who are willing to be socially engaged, there is often pressure to focus our energy on the most urgent issues of the day, rather than articulating visions of a healthy future. Yet this approach is not getting us where we need to go. Climate scientists, soil scientists, and others are giving us stern warnings about where business-as-usual leads, and it is not-at-all pretty. Also, for Maui citizens, some time spent in “rush hour” traffic on Oahu would give good reason to think about our future development options.

What could Maui be like if a reinhabitory culture were to take root? We can restore our soils, practice regenerative agriculture and grow an abundance of delicious and nutritious food for ourselves and our visitors. This holds potential to create thousands of local jobs in the farming, food, and related industries. Our electricity and transportation systems can be powered by renewable energy. Wastes and nutrients can be treated like valuable resources, recycled and repurposed rather than contaminating our groundwater and marine environment. Any new neighborhoods we build can be designed to meet present and future human needs, rather than centering around automobiles, and existing neighborhoods can gradually be retrofitted. We can strive for an active and healthy population that inhabits healthy landscapes, and a culture that centers around celebrating what makes Maui special: the island’s natural diversity and cultural richness.

This island has abundant land, water, and wealth that can be used to build a bridge to a resilient future. We have people who understand the principles and practices necessary to transition to regenerative and reinhabitory ways of living. The main impediments to this transition appear to be our ideas, our habits, and our modes of social organization. The economic and political systems we currently live within concentrate power and privilege, keep us divided, and lead to ecological degradation.

Reinhabiting Maui will take strategic organizing along multiple lines:

- promoting community self-education and important conversations;

- analyzing and understanding power relations, and the prevailing legal, political, and economic systems;

- articulating a social, ecological, and economic vision for reinhabiting Maui, and explaining how we can get there;

- engaging with and taking responsibility for local government;

- making change from the ground up, creating and supporting supporting local food and renewable energy systems, and working on projects to defend and restore nature and culture;

- finding opportunities to build unity and solidarity among different movements and segments of the community

Despite the urgency of our times there is much more to do than merely ‘resist’ – we can also work together toward reinhabiting Maui. Resist and reinhabit!

Imua! Let’s Reinhabit Maui!

Notes/References

Notes and References

The terms “Reinhabit” and Reinhabitation” have been around at least since Gary Snyder’s 1976 essay “Reinhabitation”. I encountered the terms around 1990 in the bioregional movement writings of Snyder, Raymond Dasmann, Peter Berg, Thomas Berry, Stephanie Mills and others. For a bioregional bibliography see https://kawcouncil.org/links/bioregional-bibliography/

Hānau ka Ua: Hawaiian Rain Names Collette Leimomi Akana and Kiele Gonzalez. Quote from: http://www.ksbe.edu/imua/article/haanau-ka-ua-hawaiian-rain-names-educates-and-inspires/

Ramírez-Puebla, S. T., Servín-Garcidueñas, L. E., Jiménez-Marín, B., Bolaños, L. M., Rosenblueth, M., Martínez, J., … Martínez-Romero, E. (2013). Gut and Root Microbiota Commonalities. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 79(1), 2–9. http://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02553-12

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

You must log in to post a comment.